IIHR alumnus Fred Locher has some good stories to tell about his student days at the institute.

Former IIHR Director Hunter Rouse’s Intermediate Fluid Mechanics course kept even the best graduate students in the 1950s and ’60s in awe, often tinged with fear. But it couldn’t be avoided — if you studied at the institute, you took the course. Rouse used the course to determine if the student was to be accepted for study for advanced degrees. As the legendary Rouse stood at the chalkboard, sketching fluid mechanics problems in his beautiful hand (“It was like watching the textbook being illustrated right in front of your nose,” remembers IIHR alumnus Fred Locher), most students were struggling just to stay afloat.

What they feared was that Rouse would direct a question to them, a question that could seem deceptively simple. And thus deceived, they might answer incorrectly. Rouse would then lead them down this disastrous track until they reached a dead end from which they could not extricate themselves.

It could happen to anyone, anytime.

One day, the class was talking about jets. Rouse asked a seemingly simple question. You’ve got a drinking fountain out in the hall, Rouse said. When you first open the drinking fountain, the jet squirts up higher than it does when it finally settles down to steady state. Why is that? The student unlucky enough to be asked started confidently but wandered further and further into left field. Rouse let him continue until at last the student realized — he didn’t know why the fountain behaved that way.

After watching the student flail about, Rouse asked more questions to encourage him to find a way out of his predicament. It was a harrowing experience, but an educational one, Locher says.

“You’d put two and two together and come out of it,” he explains. “That was part of your education.”

Locher, who earned MS and PhD degrees at IIHR in the 1960s, says he sat through Rouse’s course two more times after he passed it the first time. “The first time through, you were so busy trying to not fall in the hole,” Locher says.

“There were guys who were just absolutely petrified in that course because it was an experience that you hadn’t had before. Also, your future at Iowa depended on passing Rouse’s evaluation.”

Rouse, he says, insisted that students approach problems by asking themselves, what should that fluid be doing? “He wasn’t interested in teaching you mathematics. He was interested in the physical aspects of what you were seeing and what you would learn from what you saw,” Locher says.

“He was trying to get people to think! In my experience, that is the most difficult thing to do.”

PUNCH CARDS AND RUSSIAN SPIES

Locher came to Iowa in 1962 from Michigan Tech, where he had completed an undergraduate degree in civil engineering. He had an interest in hydraulics, and on his father’s advice, he applied to the strong UI program in fluid mechanics.

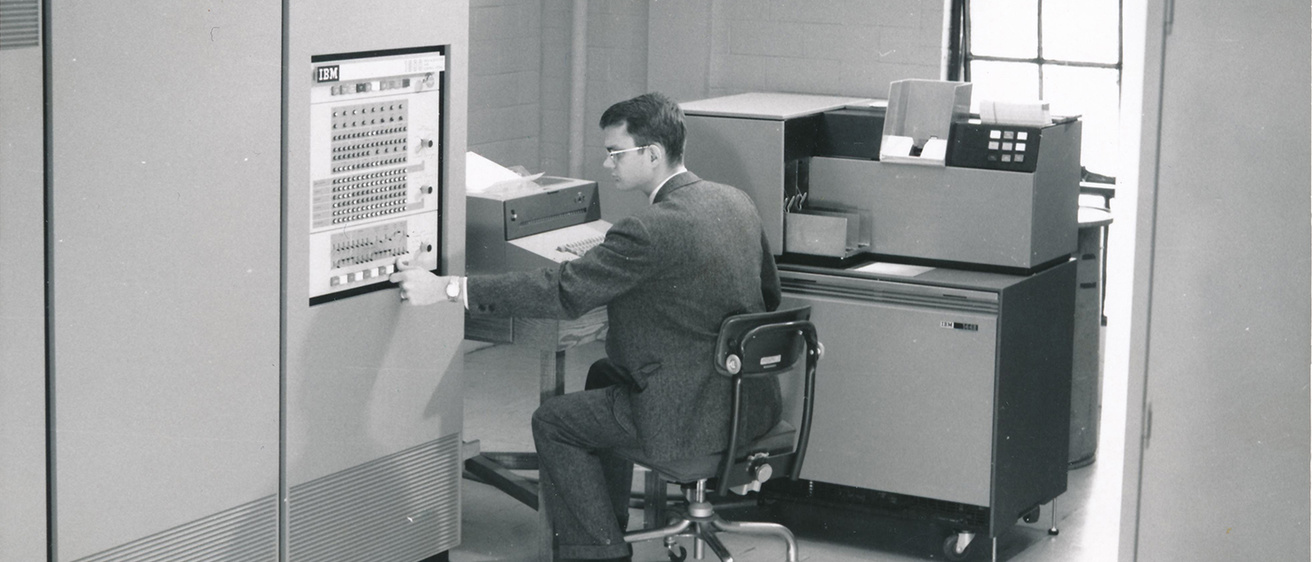

His timing was excellent. The UI physics department had just ordered a computer but then had second thoughts. IIHR Director Jack Kennedy saw an opportunity and acquired the computer for the institute. He recognized that the lab was on the cusp of a new era of research; to move forward with experimental work, IIHR needed a computer that could collect experimental data from projects in the institute’s laboratories.

Locher worked with IIHR faculty member Jack Glover (“the electronics instrumentation guru in the lab”) to set up the IBM 1800 computer. It was a milestone, one of IIHR’s first steps toward its current global leadership in computational modeling and simulation. Locher says IIHR was probably the first nongovernmental lab that had a computer that could collect experimental data, and certainly the first to do so in hydraulics.

“The Corps of Engineers in Vicksburg didn’t have this. The Bureau of Reclamation didn’t have it. Alden Labs didn’t have it, and neither did MIT,” Locher says.

IBM wanted a substantial sum of money to load out the operating system on the new computer, so Glover and Locher decided to do it themselves. The computers of that era used hundreds or even thousands of punch cards to input programs and data. “The operating system for that little machine was in three boxes of IBM punch cards,” Locher says. “A box of IBM cards contained about 2,000 cards. Do not drop!

“Of course, IBM said, ‘Well, you’ll never be able to load that out.’” Undeterred, Glover and Locher loaded out the punch cards themselves.

It didn’t run.

After some investigation, Glover soon found that the brand-new card reader was shuffling the deck of some 6,000 punch cards as it loaded them. “That meant that the instructions on the cards were getting out of order.”

Glover and Locher did “a bit of finagling” to reassemble the deck in the proper order. “We had our fair share of shuffling to do, but it finally worked!” he says. “We just straightened it out, loaded it up, and that’s how the system initially got started.”

The IBM 1800 put IIHR firmly in the forefront of the computer revolution that was overtaking science at the time. People came from government agencies and even the Soviet Union to see the new system at work. “Jack Kennedy called him our friendly Russian spy,” Locher says. “It was all on a friendly basis, but we all knew that he was really trying to find out what was going on.”

AN ELEVATING EDUCATION

Successful students at IIHR have always had to be determined and tenacious. Case in point — the elevator in Stanley Hydraulics Lab.

The elevator didn’t stop automatically, Locher says. “You kept your finger on the button. As the elevator rose up toward the floor, when it got just about right you took your finger off.” If you were good, the elevator ended up even with the floor. You opened the doors and got out.

If not, prepare to jump or try again.

“It was one of those engineering challenges,” Locher remembers. “As we said, if you passed this course, you can get out of the laboratory!”

A LIVE WIRE

Women were few and far between in engineering prior to the 1960s, but Locher remembers IIHR alumna Margaret Petersen with affection and admiration. Petersen and her friend and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) colleague Irene Miller were among the first women to take Åke Alin’s (chief USACE engineer at Fort Randall Dam) famous course on dams. “Old engineer that he was, he had a rather salty vocabulary,” Locher says. Alin was trying hard to watch his language on account of having two ladies in the room. After a couple of class sessions, Petersen finally went up to Alin and told him, “I’ve heard it all before, so don’t worry about it. Just be yourself.”

After graduating from the University of Iowa, Petersen went on to climb through the ranks at USACE, a pioneering woman in what was a man’s field. “She was really a great person, a real live wire,” Locher adds. “Anybody who survived Åke’s course was all right.”

BECHTEL AND BEYOND

Locher says the education he got at IIHR and the University of Iowa served him well throughout his career. He went on to a long and successful tenure at Bechtel, a global engineering construction firm. More than once, Locher’s ability to think saved the day.

His first boss at Bechtel was Jack Kennedy’s friend Rex Elder. “There was a fair bit of Hunter Rouse in him, though I don’t think he would admit it,” Locher says.

While he was a student at Iowa, Locher met and married his wife Donna, an Iowa native. Together they moved to California’s Bay Area, where they have lived ever since. Now retired, they enjoy sailing, photography, and travel. The pair has seen and photographed everything from African wildlife in Kenya to following in the footsteps of Agatha Christie and Arthur Conan Doyle on a mystery tour in England and Wales.

“Lessons in thinking are everywhere,” Locher says.

Still on the bucket list are the Great Wall of China and the Taj Mahal. They look forward to more trips after the pandemic — including, perhaps, a trip to Iowa in 2022 for IIHR’s rescheduled centennial?