A NASA-funded study at IIHR explores connections between reduced air pollution due to COVID-19 and decreases in precipitation in the western United States

New research at IIHR is studying the connections between reduced air pollution due to COVID-19 shutdowns and sharp decreases in precipitation in the western United States. The project, funded by a National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) RAPID grant, will provide information to support water resources management in drought-stricken areas of the West Coast.

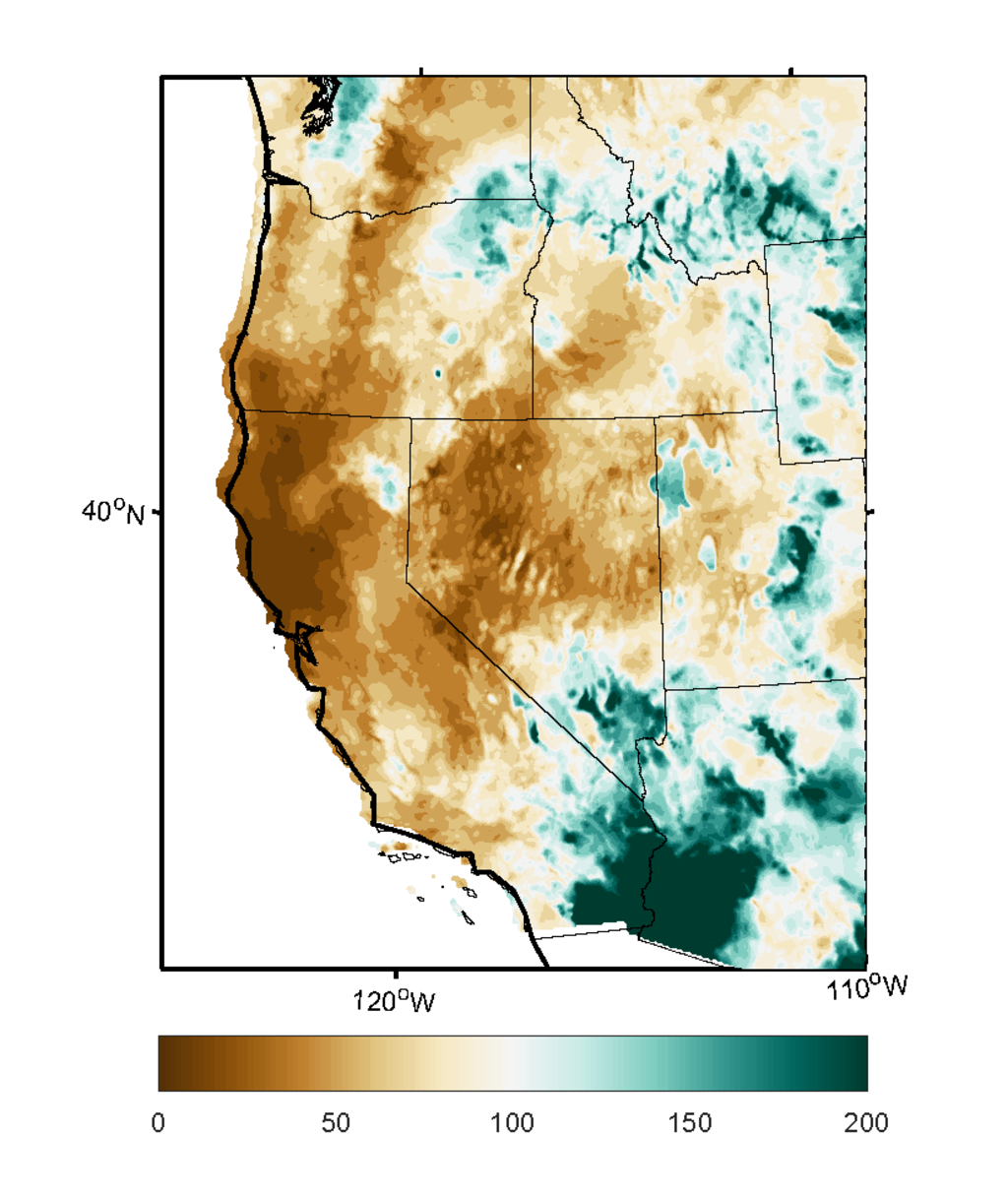

When economies shut down due to COVID-19, air quality improved in many areas. Researchers hypothesize that with fewer particulates or aerosols in the atmosphere, less precipitation fell in the western United States. In February and March 2020, precipitation dropped by more than 50%. Water resources managers on the West Coast need to know how this decrease is related to the reduction of aerosols.

Project leader Gabriele Villarini, a professor of civil and environmental engineering and director of IIHR, wants to understand the extent to which the reduction in aerosols accounts for the decrease in precipitation. “There are in a sense two drivers,” Villarini said. “One is the climate system. Some years are drier than others because of natural variability. The other is the reduced aerosols. What role do they play in explaining the observed lower precipitation amounts?”

It’s also important to know where the particulates (or lack of them) originated, whether remotely (e.g., in China) or locally (e.g., in California). Any policies enacted to mitigate the situation could have different results, depending on the source.

The project team includes former IIHR researcher Wei Zhang and graduate student Zhiqi Yang. They use WRF-CHEM, a comprehensive climate model that can combine atmospheric conditions such as moisture and temperature with chemical properties and processes.

It’s a fascinating project, Villarini says. “It’s high risk, high reward. There is a risk that the model is not going to give us enough insights and the uncertainties are too large. But the payoff, if it works, is pretty remarkable.”